This post is the first in a series of posts in which we will learn how to send messages in the Avro format into Kafka so that they can be consumed by Spark Streaming. There will be 3 posts:

- Kafka 101: producing and consuming plain-text messages with standard Java code

- Kafka + Spark: consuming plain-text messages from Kafka with Spark Streaming

- Kafka + Spark + Avro: same as 2. with Avro-encoded messages

Kafka basics

Let’s start this post with Kafka. Kafka is a publish-subscribe messaging system originally written at LinkedIn. It is an Apache project – hence open-source. Kafka has gained a lot of traction for its simplicity and its ability to handle huge amounts of messages.

I’m not going to get too much into describing Kafka. There are great articles out there such as Running Kafka at Scale and Apache Kafka for Beginners. Instead, I will focus on the keys aspects of Kafka and how to use Kafka from a developer’s perspective.

The key features of Kafka are:

- Kafka allows producers to publish messages while allowing consumers to read them. Messages are arrays of bytes, meaning you can send arbitrary data into Kafka.

- Messages are organized by topics. Messages sent into a topic can only be consumed by consumers subscribing to that topic.

- Messages are persisted on disk. The duration of retention is configured per topic and is 7 days by default.

- Messages within a topic are divided into partitions and are distributed. The idea is that a partition should fit on a single server. This allows to scale horizontally, i.e. by adding servers as you need more throughput.

- Not only messages are distributed in the cluster, they are replicated so that you never lose messages.

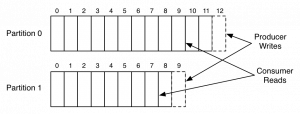

- Messages are assigned an offset. Offsets are unique and linear within a partition. It is the consumer’s responsibility to know which message it has read and which are to be consumed. In other terms, Kafka does not know about the status of each consumer. Instead, consumers have to maintain an offset per partition. That may sound strange but this is very powerful, e.g. it’s easy to process messages again by simply asking for messages from a given offset.

The picture below shows a topic with 2 partitions. The producer writes messages to both partitions (with some partitioning logic or by round-robin) and they are simply added to the end of each partition while being assigned an offset by Kafka. At the same time, a consumer reads messages from each partition.

Getting Kafka up and running

The goal here is not to provide a documentation on how to operate Kafka in production. Instead, we will start a quick-and-dirty installation with a single Kafka node and ZooKeeper (ZooKeeper is used to maintain the state of the Kafka cluster).

Start by downloading Kafka 0.9.0.0 and un-taring it:

> tar -xzf kafka_2.11-0.9.0.0.tgz

> cd kafka_2.11-0.9.0.0

Now, start ZooKeeper:

> bin/zookeeper-server-start.sh config/zookeeper.properties

[2016-02-29 15:01:37,495] INFO Reading configuration from: config/zookeeper.properties (org.apache.zookeeper.server.quorum.QuorumPeerConfig)

...

You can now start the Kafka server:

> bin/kafka-server-start.sh config/server.properties

[2016-02-29 15:01:47,028] INFO Verifying properties (kafka.utils.VerifiableProperties)

[2016-02-29 15:01:47,051] INFO Property socket.send.buffer.bytes is overridden to 1048576 (kafka.utils.VerifiableProperties)

...

We can finally create a topic named “mytopic” with a single partition and no replication. The script will connect to ZooKeeper to know which instance of Kafka it should connect to.

> bin/kafka-topics.sh --create --zookeeper localhost:2181 --replication-factor 1 --partitions 1 --topic mytopic

You may find additional details in the Quick Start of Kafka’s documentation.

Simple producer

Kafka’s Quick Start describes how to use built-in scripts to publish and consume simple messages. Instead, we will be writing Java code.

Let’s first add a dependency to our Maven’s pom.xml file:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.kafka</groupId>

<artifactId>kafka-clients</artifactId>

<version>0.9.0.1</version>

</dependency>

The 2 main entry points you will find in this library are KafkaProducer and KafkaConsumer.

Here is the complete code to send 100 messages to the “mytopic” topic we created earlier:

package com.ipponusa;

import org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer;

import org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.ProducerRecord;

import java.util.Properties;

public class SimpleStringProducer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Properties props = new Properties();

props.put("bootstrap.servers", "localhost:9092");

props.put("key.serializer", "org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringSerializer");

props.put("value.serializer", "org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringSerializer");

KafkaProducer<String, String> producer = new KafkaProducer<>(props);

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

ProducerRecord<String, String> record = new ProducerRecord<>("mytopic", "value-" + i);

producer.send(record);

}

producer.close();

}

}

Let’s describe this code:

- We begin by preparing some properties: -

bootstrap.serversis the host and port to our Kafka server key.serializeris the name of the class to serialize the key of the messages (messages have a key and value, but even though the key is optional, a serializer needs to be provided)value.serializeris the name of the class to serialize the value of the message. We’re going to send strings, hence theStringSerializer.- We build an instance of

KafkaProducer, providing the type of the key and of the value as generic parameters, and the properties object we’ve just prepared. - Then comes the time to send messages. Messages are of type

ProducerRecordwith generic parameters (type of the key and type of the value). We specify the name of the topic and the value, thus omitting the key. The message is then sent using thesendmethod of theKafkaProducer. - Finally, we shut down the producer to release resources.

Simple consumer

Before launching the producer, let’s see the code of the consumer:

package com.ipponusa;

import org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.ConsumerRecord;

import org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.ConsumerRecords;

import org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Properties;

public class SimpleStringConsumer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Properties props = new Properties();

props.put("bootstrap.servers", "localhost:9092");

props.put("group.id", "mygroup");

props.put("key.deserializer", "org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringDeserializer");

props.put("value.deserializer", "org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringDeserializer");

KafkaConsumer<String, String> consumer = new KafkaConsumer<>(props);

consumer.subscribe(Arrays.asList("mytopic"));

boolean running = true;

while (running) {

ConsumerRecords<String, String> records = consumer.poll(100);

for (ConsumerRecord<String, String> record : records) {

System.out.println(record.value());

}

}

consumer.close();

}

}

The structure is very similar to the producer’s code. Let’s see the differences:

- We have to specify the

key.deserializerandvalue.deserializerproperties, in this case Kafka’sStringDeserializerclass. - We also have to specify the

group.idproperty. It is required so as to tell Kafka which consumer group this consumer belongs to. The principle is that the consumers within a group will each receive a subset of the messages that are published, thus sharing the load. - Now, instead of creating a

KafkaProducer, we create aKafkaConsumer. - It is then required to subscribe to one or more topics by calling the

subscribemethod. - We can then query for messages using the

pollmethod of theKafkaConsumerinstance (parameter value 100 is a timeout in ms). This returns aConsumerRecordsobject which is basically a list ofConsumerRecordobjects. EachConsumerRecordobject is a message which key and value have been deserialized using the deserializer classes provided as properties.

Running the code

Time to run the code! Start by running the consumer. You should get a few line of logs and the process should then wait for messages:

2016-02-29 15:27:12,528 [main] INFO org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.ConsumerConfig - ConsumerConfig values:

...

2016-02-29 15:27:12,707 [main] INFO org.apache.kafka.common.utils.AppInfoParser - Kafka version : 0.9.0.1

2016-02-29 15:27:12,707 [main] INFO org.apache.kafka.common.utils.AppInfoParser - Kafka commitId : 23c69d62a0cabf06

Then, and only then, launch the producer. The output should be very similar, and then end with a line saying the producer has been shut down:

2016-02-29 15:27:54,205 [main] INFO org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer - Closing the Kafka producer with timeoutMillis = 9223372036854775807 ms.

If you go back to the consumer, you should see some output on the console:

Value=value-0

Value=value-1

...

This seems to work as we would have expected. A few things to note, though. First, we said earlier that the offsets were managed by the consumer but we didn’t do anything regarding offsets. That’s because, by default, the KafkaConsumer uses Kafka’s API to manage the offset for us. To manage offset by hand, you should set the enable.auto.commit property to false and use the seek method when initializing the KafkaConsumer.

In our example, the consumer queries Kafka for the highest offset of each partition, and then only waits for new messages. If we had started the producer before the consumer, the messages would have been silently ignored.

Now, this was a very basic example as we were only using one partition. We can update the topic so that it uses 2 partitions:

bin/kafka-topics.sh --zookeeper localhost:2181 --alter <b>--partitions 2</b> --topic mytopic

As we said earlier, the producer can decide to which partition it wants to write to. This is done with an extra parameter to the ProducerRecord constructor. The documentation is pretty clear about the behavior:

If a valid partition number is specified that partition will be used when sending the record. If no partition is specified but a key is present a partition will be chosen using a hash of the key. If neither key nor partition is present a partition will be assigned in a round-robin fashion.

On the side of the consumer, all the consumers that have subscribed to the topic and that are within the same group will receive a subset of the messages. If we were to create 2 threads, each with a KafkaConsumer, each consumer would most likely receive the messages of one partition.

Conclusion

We’ve seen the basics of Kafka, how we can publish and consume messages with a simple Java API, and how messages can be distributed into partitions. This partitioning is one of the features that allows Kafka to scale horizontally.

In the next post, we will see how to use Spark Streaming to consume messages from Kafka.