Ah, technical debt. There’s something to be said for throwing scalability to the wind and developing your application in record time as a monolith with a single datastore. After all, your customers are demanding new features, the investors want a speedy return on their money, and your competitors aren’t going to wait around to take your market share.

But now that you have gone live, success is becoming your enemy. Database locks are plaguing performance. Making changes in your Bar Module causes your Foo Module to break. Your developers dread having to figure out where to stick the scalpel to fix all this, and your scrum stand-ups are going into overtime trying to figure out a solution. All too often band-aids are applied to the system to fix problems as they emerge. As these band-aids pile up on top of each other, the code base becomes a mess and other problems arise.

If you have started to analyze turning a monolithic app into something scalable, you have probably considered the microservices architecture. In the Java world, the latest Spring Boot releases offer a lot of out of the box libraries to support this architecture, and code-generation frameworks like JHipster can create a sophisticated CRUD microservices app with all the latest bells and whistles in a matter of minutes.

It sounds good at first, but once the tradeoffs start to emerge between data consistency and system availability, even the most adventurous CTO can be found curled up into the proverbial fetal position. That’s too bad because, once a system starts to deadlock, more dramatic compromises have to be made. That compromise often comes down to rethinking the way we view consistency and availability with our data.

The Absolute Equivocal Importance of Data Consistency

Let’s use the example of an e-Commerce store to illustrate the point. We sell fuzzy sweaters online at a variety of store fronts. Since we don’t have a brick and mortar operation, we can technically sell anywhere: our own website, that online auction warehouse that allows POS, a former online-bookseller turned global domination behemoth, etc. However, we keep all 100 of our fuzzy sweaters in one warehouse and tell all our vendors that 100 is what we have available. Well that is great, except we sold 30 sweaters in store A, 30 sweaters in store B, and 35 sweaters in store C… meaning there are just 5 sweaters left. However, stores A and B think there are 70 sweaters in stock, store C thinks there are 65. We can send an inventory update to all three stores to let them know there are only 5 available, but how long will that take?

If we have to scan the database for all orders and then scan our warehouse table in the same database for the current available inventory to calculate the total number, there’s a good chance we may not have access to the most recent values in either table if we’re doing a lot of work there. If another transaction has the database tied up and our transactional level is set restrictively, the problem could be worse. We want to have the most accurate inventory number to push to the sales channel (5 in this case), but by the time it gets there, what if each store front sells two sweaters a piece? We just oversold our inventory by one whole sweater and, in the time it takes to recalculate the new value and push it to the server, we could be in big trouble!

By refactoring this application into a microservice architecture, we can divide the logic into separate systems, an orders microservice and an inventory microservice, with their own datastores. However, we now have to consider the latency in having the inventory service contact the orders service. Is the orders service sending us back the latest data? What if the orders service is not available when we need it or goes down completely?

Enter CAP Theory

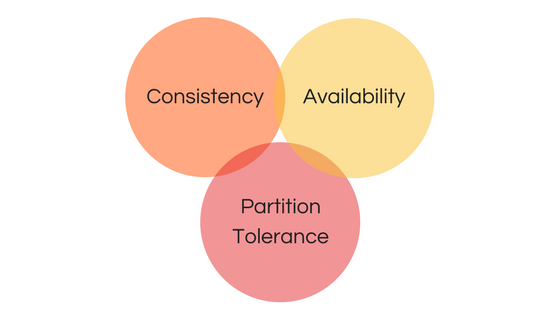

The problem I am describing here has been analyzed by Computer Scientist Eric Brewer, who developed the CAP Theorem to discuss the problem we are dealing with. CAP is designed to reflect the tradeoff between:

Consistency: every read receives the most recent write from our datastore(s).

Availability: every request receives a meaningful response.

Partitioning: the system will continue to operate despite outages between different components of our network.

More specifically, the CAP theorem offers the principle that we can only provide two of these ideal characteristics in a distributed system.

If we’re not guaranteeing consistency of our data, we can have a system that is highly available across multiple nodes, and we can easily scale to handle any number of requests. It’s just that those requests need to be aware that they may not be looking at the latest and greatest data.

If we’re not guaranteeing absolute availability of our system in peak times, then we can enforce the integrity of our data, allowing one of our network partitions to handle the request, but we may need to return a “Service Unavailable” style response while we coordinate data and events across our different services and nodes.

Forsaking partition tolerance, we are basically returning to our monolithic architecture. Essentially, we’re writing desktop applications that don’t connect to the Internet or cloud apps that do not need to scale. Lame. Next!

Since the point of this post is to talk about refactoring cloud-based monolithic systems into cloud-based microservices, sacrificing our ability to partition the system is not an option. That means that, were we to pick one other aspect to maintain according to our 2-out-of-3 CAP Theorem idea, we have to sacrifice data consistency or system availability. However, it’s kind of silly to say we should only have one or the other so, as is the case in any discipline of engineering, even computing, we have to consider the trade-offs (I should also mention that when working with a poorly designed system, we are not guaranteed to even have two-out-of-three available). So let’s consider how we can make a system that is highly available but lacking in data consistency or, rigidly has to enforce consistency at the expense of being able to provide this data to clients in real-time.

Balancing Consistency with Availability

Let’s return to our original example of the e-commerce store. Remember we refactored our monolithic application to have two microservices. One to manage orders from the stores we sell to, the other to manage the inventory of the products we sell. In the old system, our orders and inventory information existed in the same database, so theoretically our inventory module could make adjustments for orders as they were written in real-time. If we separate orders and inventory into their own microservice applications with their own databases, we enter into uncertain territory.

Our inventory needs to be able to get the current state of orders as they come into the system, are canceled, shipped out, etc. But the information we get from the orders microservice is only as good as its availability and consistency. What if the numbers we are receiving from the orders service is too old to account for recent activity in the last few seconds, minutes, or even hours? What if some catastrophe occurs and the orders service goes down completely for an unspecified time? The Inventory microservice’s dependency on an outside system, even if it is one of our own, means absolute atomic consistency is not going to happen. We want our inventory microservice to be highly available as it will always need to provide inventory updates to marketplaces requesting that information, so we need to consider how our system can thrive in an uncertain environment.

When you accept the limits of consistency in an environment you can start the fun part of software development: engineering! With our inventory system we want to protect against selling product that we no longer have so we can detect situations where stock levels are dropping low and only push the last known inventory to the most popular storefront, and 0 to the rest. If this solution is not robust enough, we can start tracking the velocity at which our inventory drops over time and use those numbers to project stock out situations and handle them accordingly. Different items in our warehouse may need to use specific strategies vs others. Implementing these solutions in a monolithic architecture means lots of code in a system that is hard to maintain but works much better in a well-organized microservice environment.

Balancing Availability with Consistency

From the perspective of our Orders microservice, we might face the opposite problem: Now that we have exclusive read/write access to our database our information is highly consistent, but due to a large volume of requests submitting new orders to our system and a large volume of requests wanting to read the information from these orders, availability of the system could be problematic.

Let’s say we receive a request for all valid orders that arrived within the last 15 minutes. At the same time, we run all new orders into the system through our fraud detection algorithm, validate the destination addresses of the order, etc, before writing the orders to the database in batches. This could mean writing the orders to the database in their raw state, accessing this data later in a repeatable-read format to validate the information before updating it with the finalized information.

To balance the needs for highly consistent data with consumers that want to know about it, we might consider a messaging queue service that publishes events every time a new order comes in and every time it is updated. Maybe we employ a restrictive throttling-policy on all read requests on our RESTful API using a leaky bucket algorithm and add a feed-based call to return large amounts of data at once.

Wrapping Up

Simply using a microservices architecture will not magically make your application more scalable. In fact, if we don’t consider the tradeoffs and measure the balance between data consistency and service availability, it could be worse. Properly understanding the limitations of a given system and engineering around its bottlenecks is going to be key. Fortunately there are a lot of data structures, libraries, and technologies to assist in this endeavor.